Yesterday I bought the commercial edition of Binary Ninja and I wanted to test it out so I went looking for some interesting reverse engineering challenges. Since I SUCK at reverse engineering I decided to go for a simple crackme from the 2017 edition of the Enigma CTF called Crackme 0. I could’ve looked at the provided C source code but what’s the point in reverse engineering if you already have the source? Let’s leave source codes to whitehats, shall we?

Static analysis with Binary Ninja

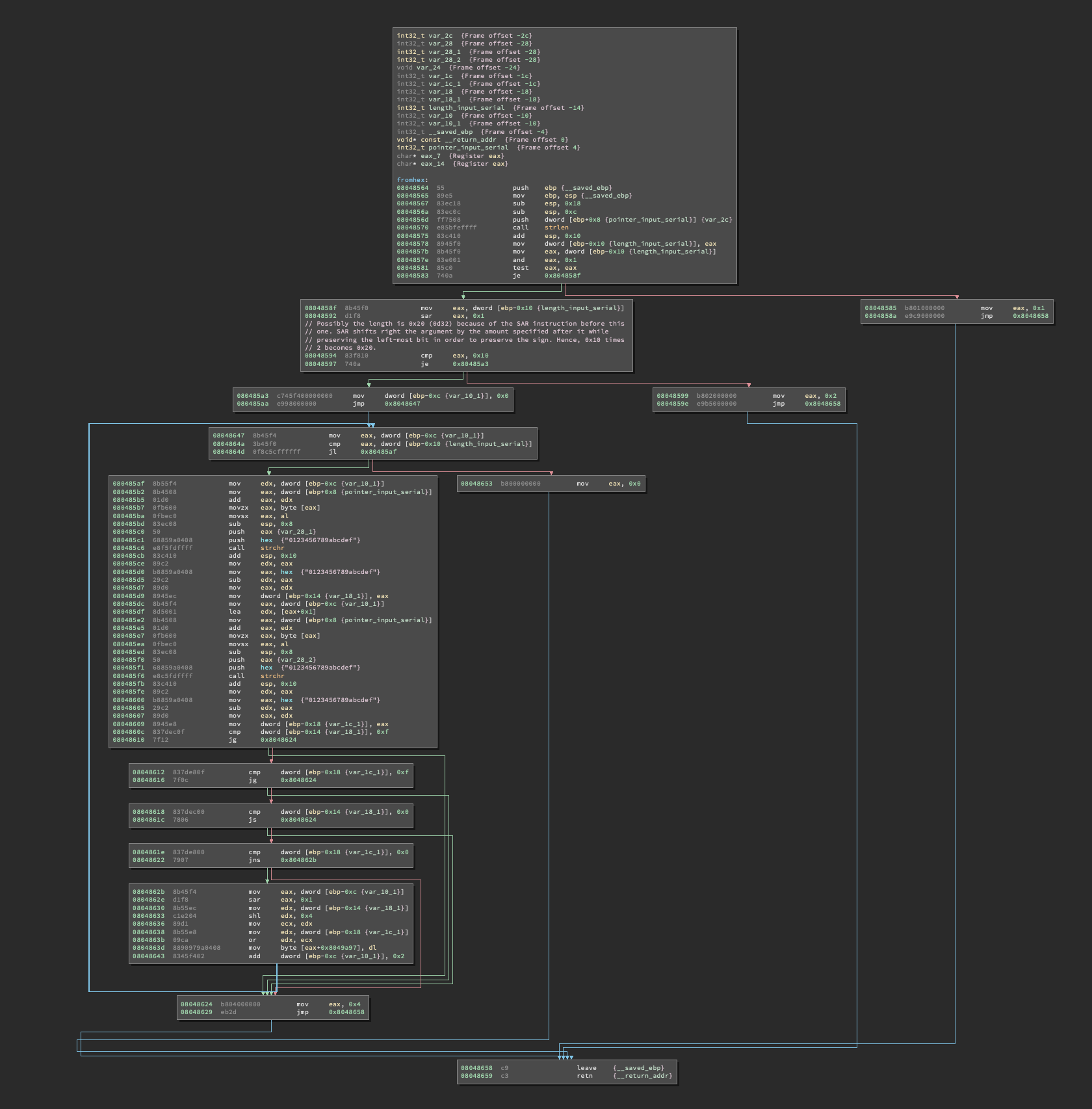

First things first, I fired up my good friend Binary Ninja (Binja from now on) and started looking around the binary. Other than main() we have three interesting functions:

- wrong()

- decrypt()

- fromhex()

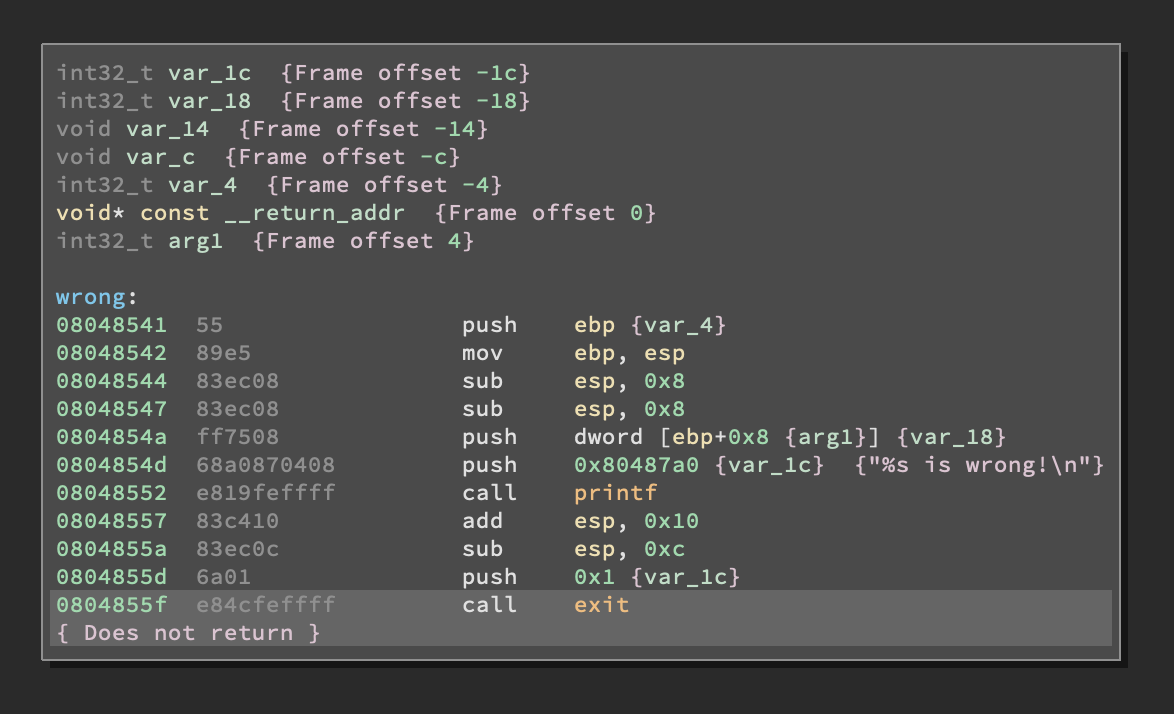

Let’s start with wrong()

Meh. It doesn’t do much except for killing the process. From the Cross Reference (XREF) section of Binja we can clearly see it gets called twice from main.

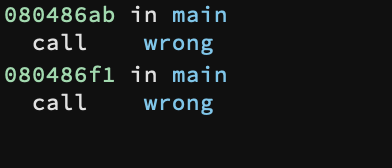

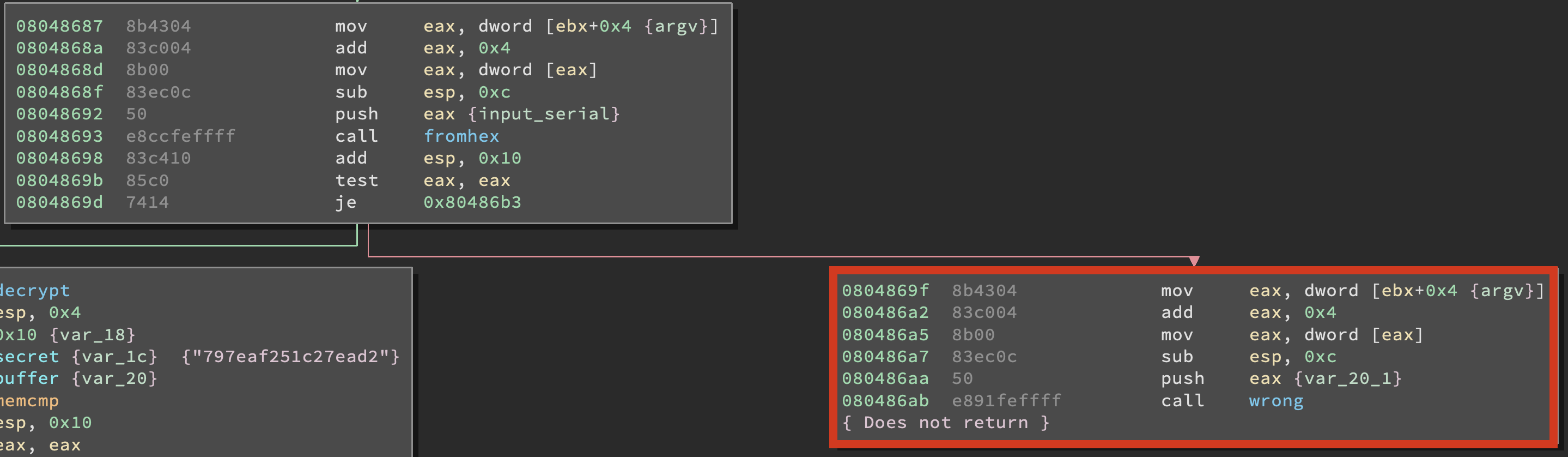

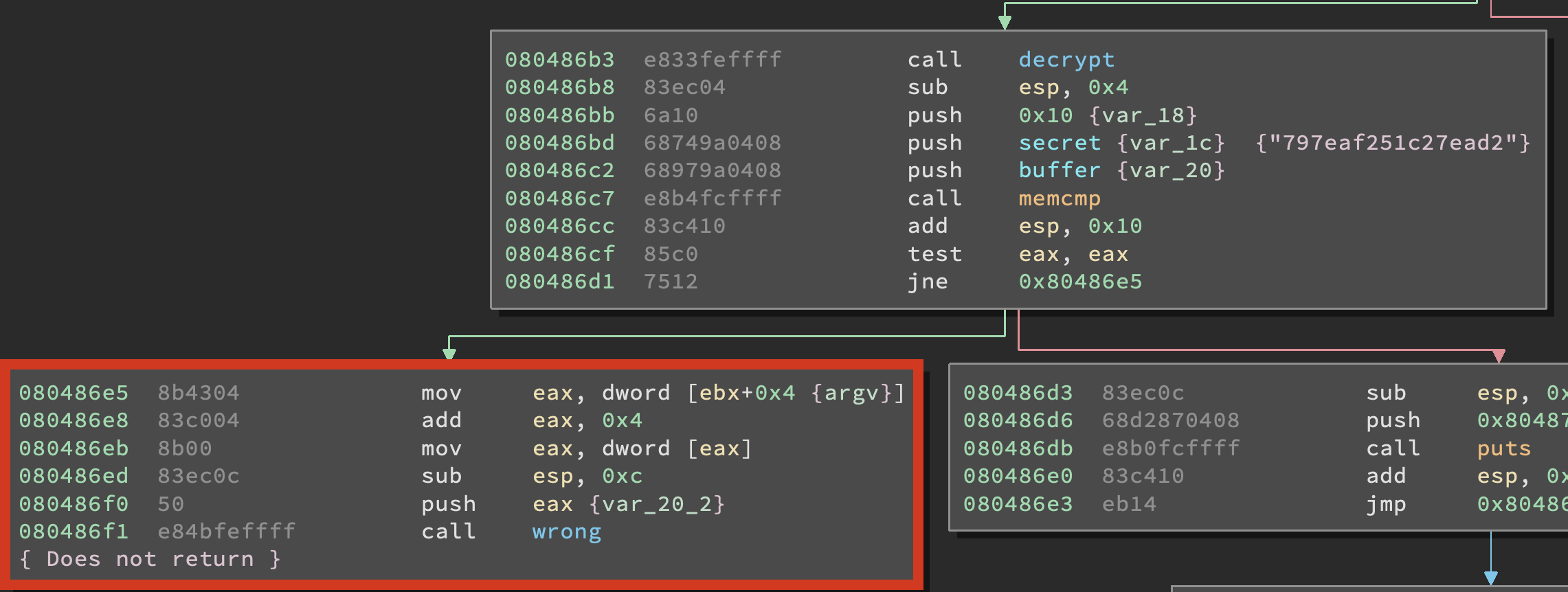

While doing reverse engineering it’s always important to look at failure functions like wrong() and when they get called because it can shed some light on how the program works and, more importantly, what are the conditions for it to work properly. What you have to look at specifically is when functions like wrong() get called. As we said before it gets called twice: once right after the fromhex() function returns.

and the second time right after an interesting memcmp() call.

But let’s do things the tidy way, after all this CTF ended two years ago so we are not competing. Time to open up the fromhex() function and see what it does.

Oh boy, I hate when things get messy out of nowhere… Let’s go with the cartesian logic approach: we will break it down into smaller blocks and see if we can work out what’s happening here.

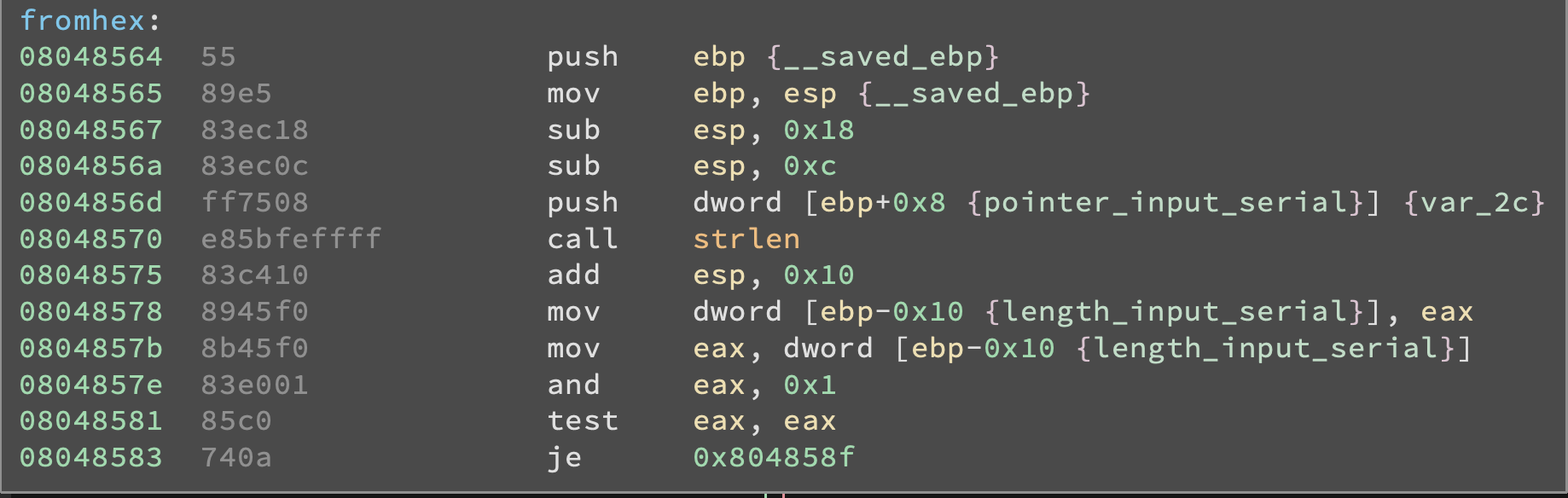

What this block of fromhex() does is essentially setting up the stack right after the function call and checking the length of the input string calling the C function strlen(). I already changed variables’ names in Binja in order to make it easier to understand which areas of the stack point to which variables. Per calling convention, when a function returns the return value is put into EAX and indeed you can see that, right after strlen() returns, what’s into EAX is copied into a local variable positioned at EBP-0x10. If we check the manpage for strlen() we can find the following information:

So… strlen() gives us back the length of the string it takes as argument. That’s interesting, in fact most of the times a programmer will check if the length of the string it’s right before even checking the string! So we can assume that right after the strlen() call we will find an instruction comparing the length of the string with a fixed value. And that’s exactly what happens.

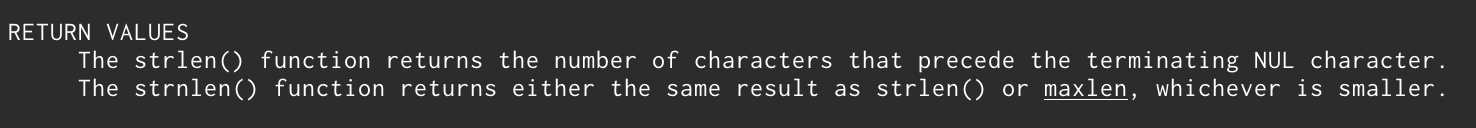

I commented the code as it took me a while to clearly understand what’s happening here. I HAVE NO IDEA WHY but instead of checking directly the length of the string with a CMP EAX, 0x20 the program first uses a SAR EAX, 0x1 instruction to divide by two the length of the string and then does a CMP EAX, 0x10.

EDIT: Hi, last from the future here. After almost finishing writing the post I decided I would finally take a look at the source code to make sure I didn’t leave anything interesting uncovered and it turned out there was a reason for the program to do this: in the source code there were the following lines:

int len = strlen(input);

//can't decode hex string with odd number of characters

if (len&1) {

return 1;

}

//make sure len/2 is the size we are looking for

if (len>>1 != SECSIZE) {

return 2;

}

So, what’s happening here is the program first checks if the string is made of a even number of characters (by doing len&1 it does a bitwise AND with 0x1, thus checking if the right-most bit is a 1 or a 0) and then divides len by two and checks if it’s equal to SECSIZE (which is defined as 16 earlier in the code). Now back to past last’s writeup.

NOTE: the SAR instruction stands for Shift Arithmetic Right and takes two arguments: the first is the destination and the second is a numeric value. What it does is essentially shifting right the bits inside the destination by an amount specified by the numeric value, but preserving the left-most bit. In this way the sign of the number contained by the destination doesn't change but the value gets divided by two to the power of the numeric value.

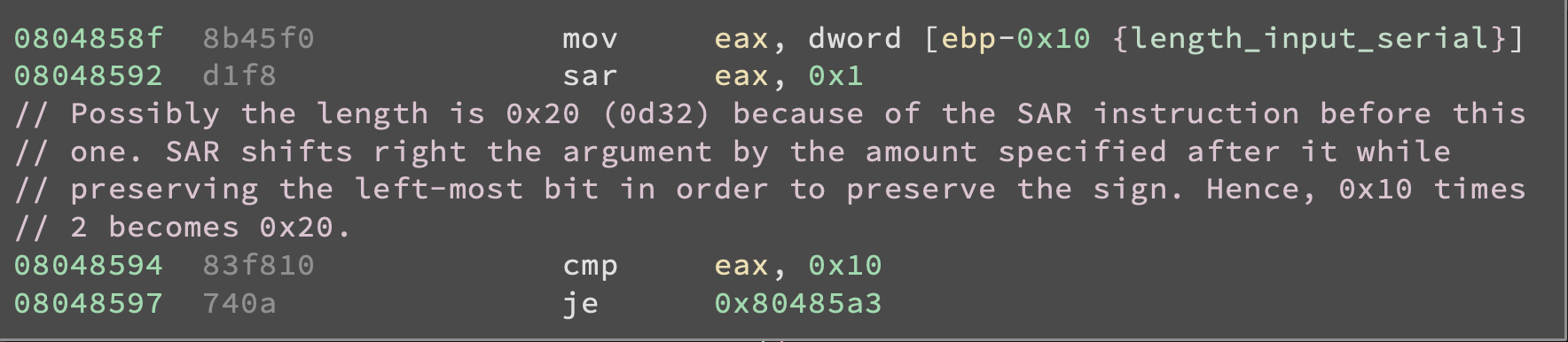

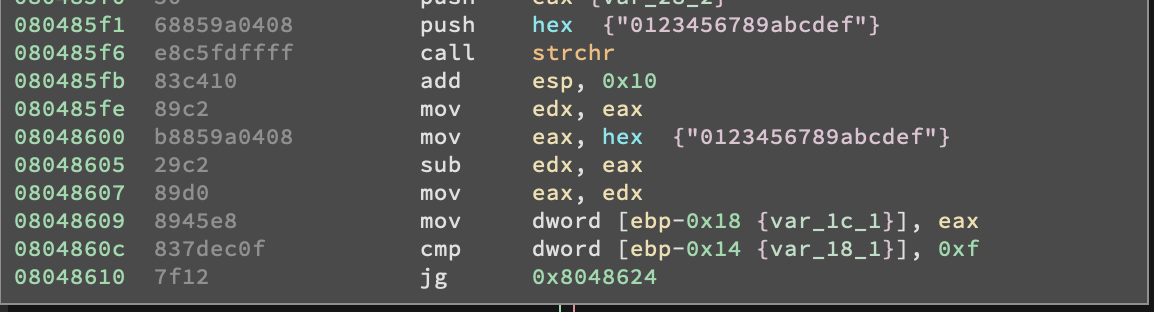

By looking at the rest of the fromhex() function it seems like its sole purpose is to check whether the serial number we input is a valid hexadecimal string

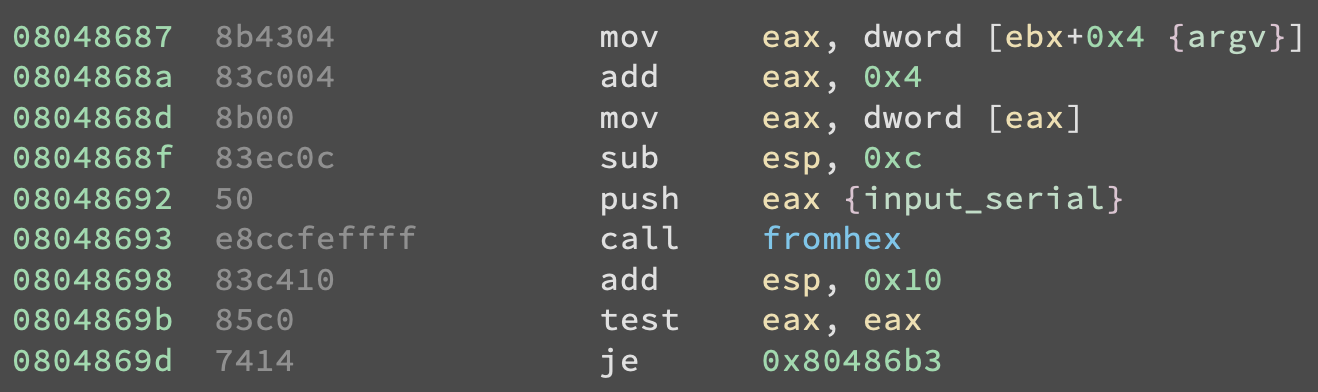

Also we can see that the fromhex() will return a non-zero value everytime it finds a non hexadecimal character inside our input string or if the input string is not 32-character long. That’s interesting, note that main() will check what the return value of fromhex() is (by checking the content of EAX via TEST EAX, EAX) and if it’s not zero will jump to the code block that leads to wrong().

The address in the instruction JE 0x80486B3 is the address of one of the code blocks that lead to wrong().

Ok, let’s do a quick recap of what we know so far:

- the program wants a string as argument

- the string must contain exactly 32 characters

- the charset is [a-z0-9]

- failure to comply with the requirements above leads to

wrong() - the function

fromhex()is responsible for doing some of the above checks

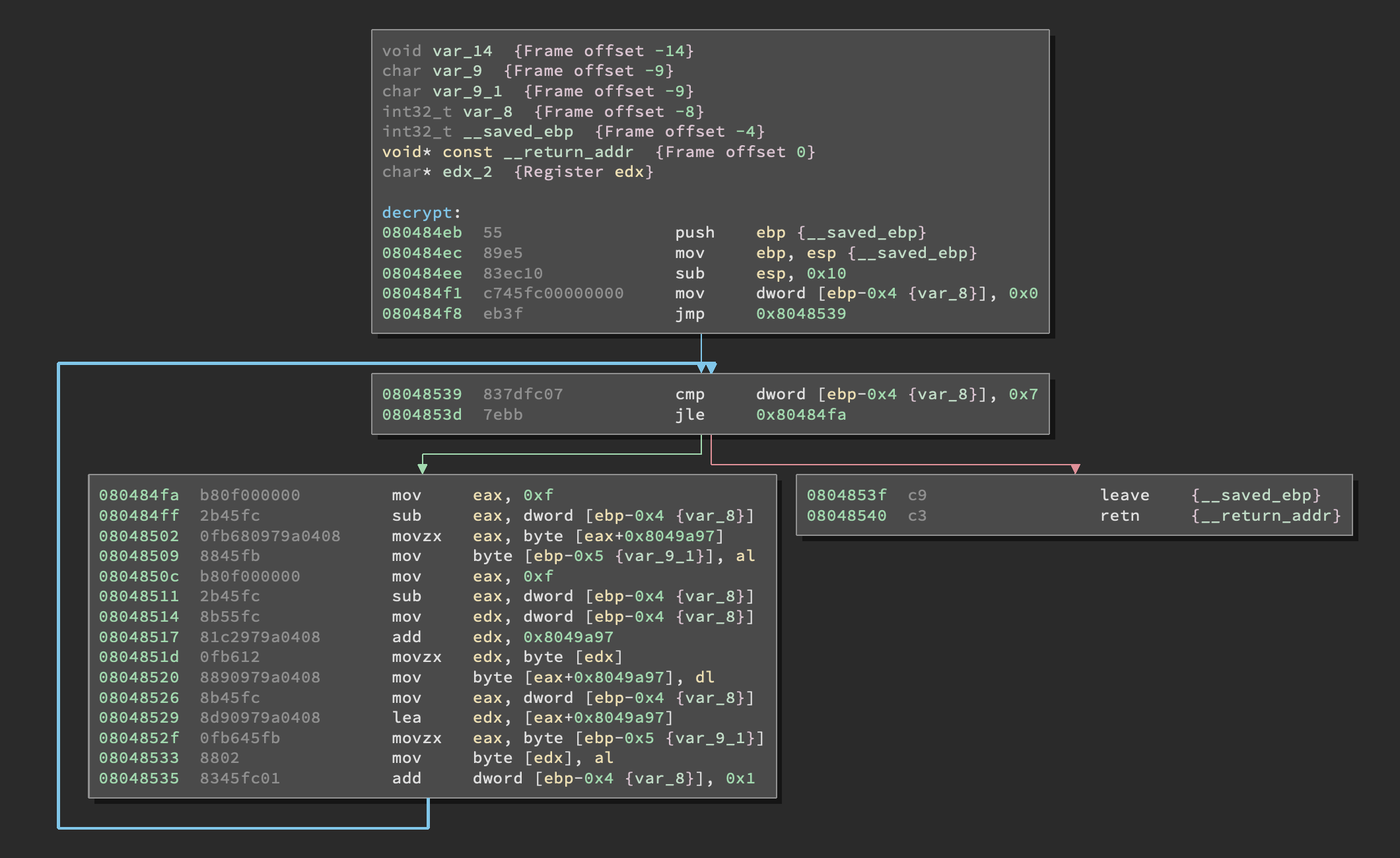

Now that we understand the program a bit better we can move on to the more interesting (and usually scarier) function decrypt().

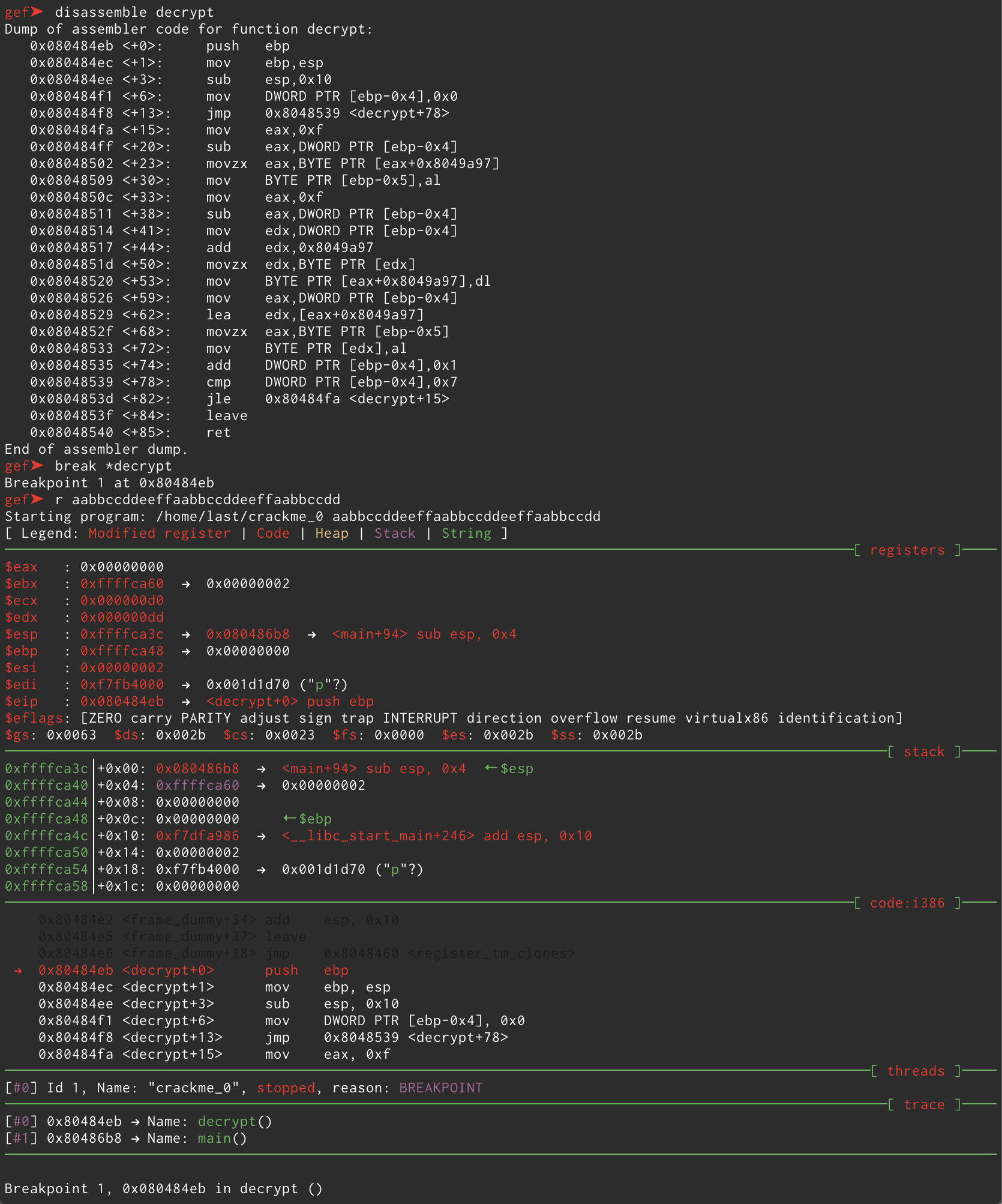

You know what mate? I’ve seen worse, this one even fits the screen! Wanna know another thing mate? I’m a little bit tired of looking at static assembly code, why don’t we analyze the workings of this function using our good friend GDB? I’m going to cheat a little bit and use GDB Enhanced Features (aka GEF) which is a set of commands for GDB that adds a lot of functionalities and also formats the output in a better way using color codes and stuff like that.

Let’s declutter this a bit. In this screenshot you can see I

- disassembled the

decrypt()function viadisassemble decrypt - placed a breakpoint at the beginning of the function via

break *decrypt - ran the program with a 32 byte string via

r aabbccddeeffaabbccddeeffaabbccdd

And as expected the execution stopped right at the beginning of decrypt(). As you can see the string we gave as argument to the program respected all the requirements we defined above and allowed us to breeze through fromhex(), otherwise the program would’ve told us our input was wrong and wouldn’t even have reached decrypt(). That being said let’s step through the function and see what happens to our input. After letting it do its stuff for a few rounds I notice the address 0x8049a97 is being called more than once by the following instructions inside decrypt():

movzx eax, BYTE PTR [eax+0x8049a97]

add edx, 0x8049a97

mov BYTE PTR [eax+0x8049a97], dl

lea edx, [eax+0x8049a97]

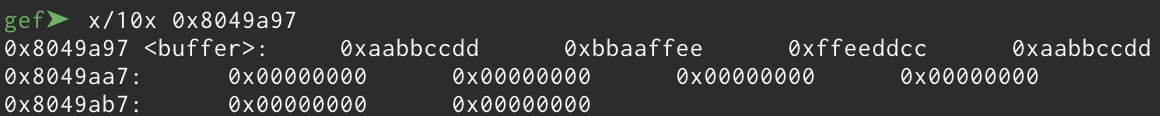

It seems like it’s manipulating some kind of string, and that makes sense since the function is called “decrypt”. Let’s check what we can find at that address:

That was unexpected. It seems like the function is converting our input string to a block of bytes, two characters at a time… That makes perfectly sense! Think about it: our input string was 32 bytes and the charset is [a-z0-9] which is the same charset of hexadecimal numbers, if decrypt() converts it into bytes we will have 16 bytes, every byte will be made of two characters from our input. Also this address in memory has a name: buffer. Why does it sound familiar?

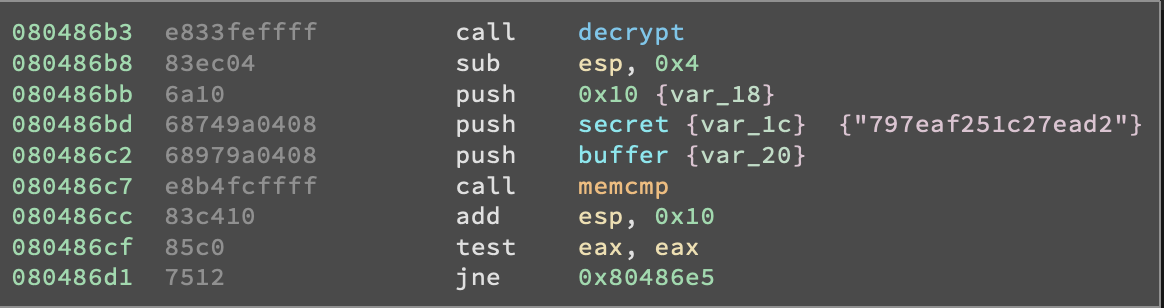

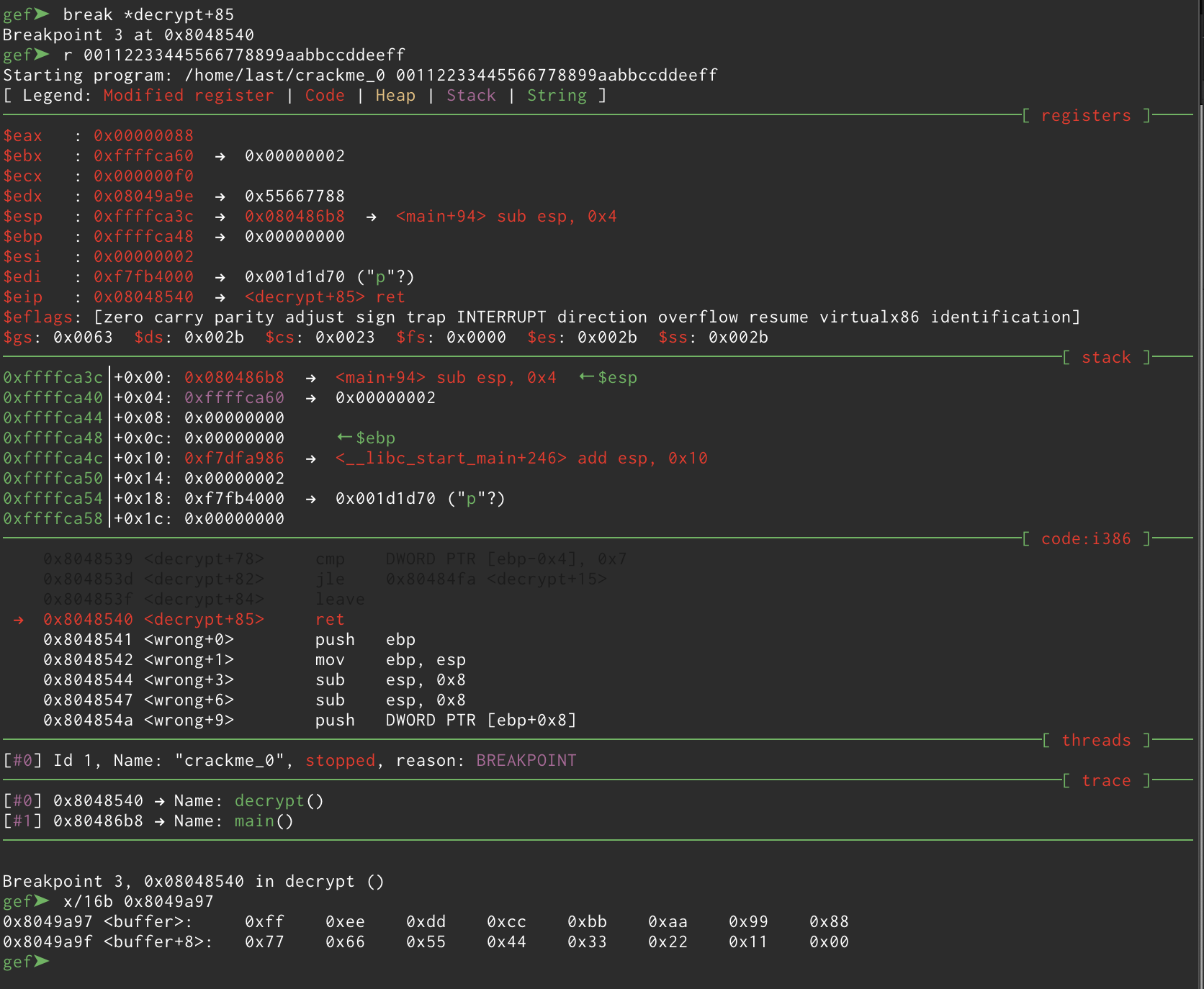

That’s right! Remember that “interesting” call to memcmp() we mentioned before? It seems like this buffer variable will be compared to a secret variable. Let’s get back to decrypt() and check how buffer is modified. I will now place a breakpoint at the end of the function and run the program again, this time with 00112233445566778899aabbccddeeff as input.

Now it’s really clear! As you can see in the lower part of the screenshot our input has been parsed and we went from this

0xffffcd01: "00112233445566778899aabbccddeeff"

to this

0x8049a97 <buffer>: 0xff 0xee 0xdd 0xcc 0xbb 0xaa 0x99 0x88

0x8049a9f <buffer+8>: 0x77 0x66 0x55 0x44 0x33 0x22 0x11 0x00

Interestingly our string is parsed using the little-endian format which specifies the right-most byte is placed at the lower address. Now that we know that, the last thing to do is to analyze the part of the program that leads to the memcmp().

We know that memcmp() is a C function that takes three arguments:

- a pointer to a block of memory

str1 - a pointer to another block of memory

str2 - a number

n

What it does is essentially comparing the first n bytes of the two blocks of memory str1 and str2. It can return the following values:

- less than 0 if

str1is less thanstr2 - more than 0 if

str1is greater thanstr2 - equal to 0 if the two are the equal

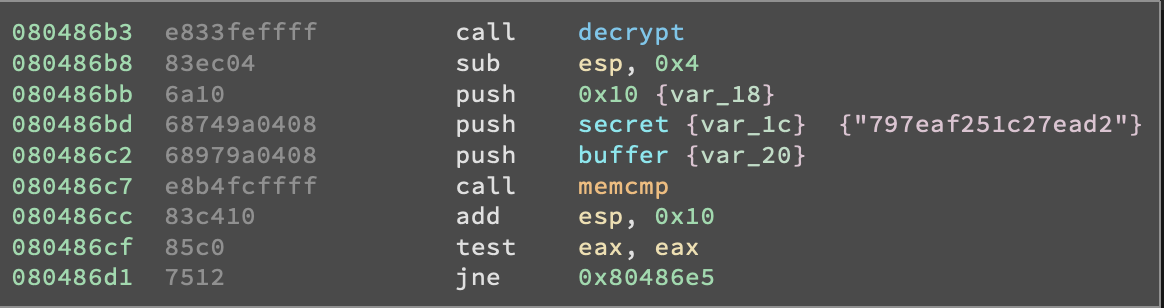

So, by looking at the assembly we can see that three arguments are pushed on the stack before calling memcmp() and those are the number 0x10, the address of secret and the address of buffer. Since we know the calling convention states that arguments are pushed on the stack in reverse order we know that ther number 0x10 is the amount of bytes to check and that secret and buffer are the two blocks of memory that will be compared. And judging from the JNE 0x80486e5 now we know that buffer and secret must be the same in order for the function to print the string “That is correct!”.

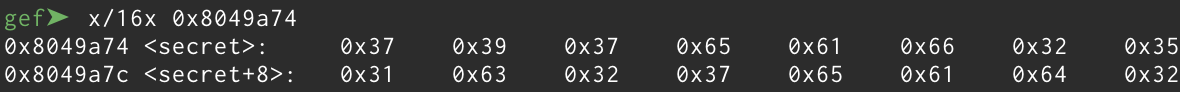

Knowing all that we can now simply go in memory and check what secret looks like. We can find the address of secret by disassembling main in GDB and seeing which address is pushed on the stack before buffer is pushed on the stack and memcmp() is called.

Perfect. Now we only have to rewrite our input so that it gets parsed in the right way. Knowing the value of secret all we have to do is write it backwards so that we get from this

0x8049a74 <secret>: 0x37 0x39 0x37 0x65 0x61 0x66 0x32 0x35

0x8049a7c <secret+8>: 0x31 0x63 0x32 0x37 0x65 0x61 0x64 0x32

to this

32646165373263313532666165373937

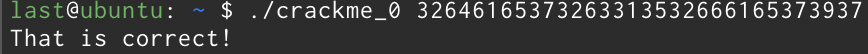

and in fact when we run ./crackme_0 32646165373263313532666165373937 we get the following output

Ok, now I gotta be honest with you. I’m notso.pro and it really didnt’t go that way so I’ll do a quick rundown of how things really went.

What's all this mess?

WTF am I still doing here?!

FUCK!

FUCK!

FUCK!

Ehi look there's a string there!

It's not the serial!

FUCK!

FUCK!

FUCK!

This shit doesn't work!

FUCK!

FUCK!

FUCK!

I really suck at this!

FUCK!

FUCK!

FUCK!

Wait a minute, my input is translated to this stuff?

So that's how it works uh?

Great I solved it!! Now, how does this shit work?

Yeah. Just like that. Oh, did I forget to tell you it was 4AM when I finally solved it? Yeah, my life kinda sucks.