To my good friend Vito and to the league of evil men.

Let’s do some black wizardry, shall we?

There is a well known thought experiment that makes one wonder whether a tree falling in a forest, with no one around to hear the sound of it hitting the ground, actually makes a sound at all. Well, I don’t know about you my friend, but I know nothing about trees falling and botany in general! What I do know however is the sound some people make (sysadmins, mostly) when they see a entire forest go down. Yep, I’m talking Active Directory forests. Trust me, it’s traumatic.

Ok, now that I have overtaken blank page anxiety (bear with me okay?) we can start talking more seriously. Recently I was involved in a internal penetration test of a big organization which had networks spread across many European countries. It was a multi-step operation, with my work being the second step, after the initial compromise performed by other guys who landed a shell on the frontend through a web application. Long story short, the operation was a big success (full compromission) because of some basic misconfigurations of their Active Directory environment. Stuff like this happens very often as AD is not easy.

|

|---|

| Yep, that’s how it felt! |

And here we arrive at the reason for this (short?) blog post series. Despite what some good friends of mine say (gne, @Th3Zer0 and @Smaury?) Active Directory is really interesting as a target, as it’s a complicated mess of technologies and practices which technicians get wrong a Shitton™ of times! What I want to cover in these posts is the workings of the components that make (and often break) Active Directory environments. We will start slow, analyzing the components themselves and then how they fit in the grand scheme of (offensive) things.

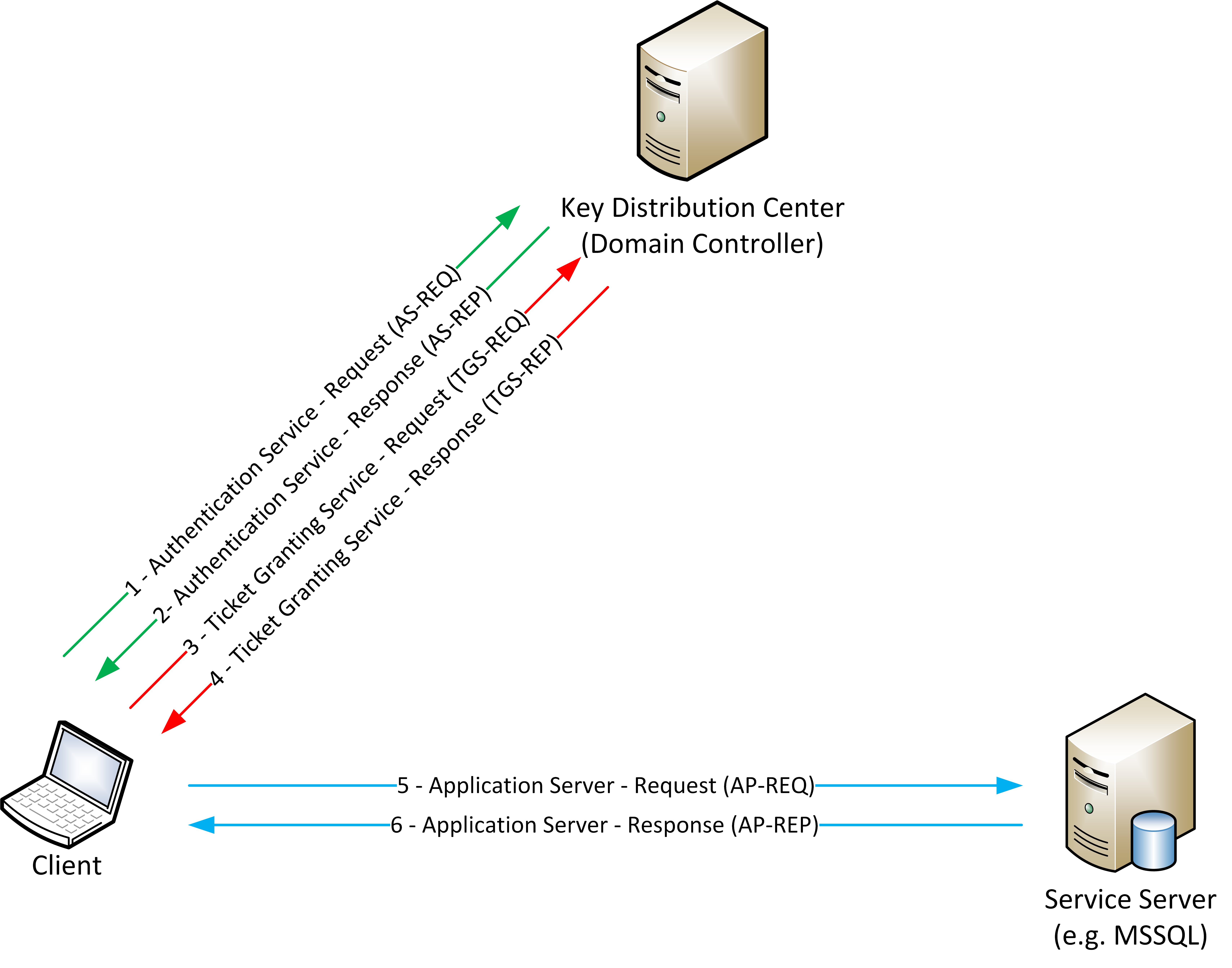

In this part (which is the zeroth one) we will have a look at how the infamous Microsoft’s implementation of the Kerberos authentication protocol works, step by step. The idea of the series is to analyze each step, understand the assumptions behind it and how to turn those assumptions against our target. But first, da fuq’s Kerberos?

High level overview and terminology

At its core, Kerberos is an authentication protocol, period. It was first devised by the MIT, then Microsoft decided to use it (after customizing it a bit) as the basis for authentication across Active Directory.

|

|---|

| I suck at Visio, don’t hate me… |

At first it can seem complicated, but it really isn’t. Kerberos revolves around three main concepts:

- The Key Distribution Center (KDC)

- Tickets

- Shared secret

Let’s briefly discuss them. The KDC is the server responsible for authenticating the clients. In Microsoft’s implementation of Kerberos, the KDC and the Domain Controller (DC) are the same machine, and from now on we will refer to the KDC as simply the DC. In Kerberos, clients do not directly connect to the service server (the machine that has the resource they want to access), they first have to request a ticket from the KDC.

So what’s a ticket? Simply put, a ticket is a piece of information, structured in a particular way, the client holds in memory. It becomes an authentication token the client provides to the service server so that the server can verify whether the client can access the resource or not. But how does a client request a ticket? It makes a special request encrypted with a shared secret that only the client and the DC can know.

The shared secret, in Microsoft’s implementation of Kerberos, is the NT hash of the user’s password. For those of you wondering what a NT hash is: it’s the official name of what’s misleadingly known as NTLM hash. We will use the name “NTLM hash” from now on as its usage is widespread, but check this post for a more complete overview of the different hashes algorithms Windows implements. How does the client and the DC know the shared secret without exchanging it before? Well, the client knows it as it is the NTLM hash of the user’s password, while the DC knows it because it stores the passwords’ hashes of all the users of the domain (duh?). As a reminder, the NTLM hash of a string is calculated using the following formula:

MD4(UTF-16-LE(string))

Which stands for the MD4 digest of the string encoded in the UTF-16 little endian format.

Kerberos authentication step by step

Ok, now that terminology is out of the way, let’s get to the authentication mechanism. I suggest you follow this while keeping along a tab with the RFC 4120, which is Kerberos’ RFC, open. As we already said, before accessing a resource, a client needs to interact with the DC to get the information he needs in order to show the service server who he is (or, more precisely, claims to be). As you saw in the previous image, the Kerberos authentication mechanism is comprised of six mandatory step and two optional steps (I didn’t draw the optional ones, as they are out of the scope of this series). The steps are numbered from 1 to 6:

- Authentication Service - Request (AS-REQ)

- Authentication Service - Response (AS-REP)

- Ticket Granting Service - Request (TGS-REQ)

- Ticket Granting Service - Response (TGS-REP)

- Application Server - Request (AP-REQ)

- Application Server - Response (AP-REP)

The odd numbered steps are initiated by the client, while the even ones by the DC. The two optional steps involve the service server verifying certain information provided by the client but this check is rarely enabled as it adds a ton of overhead to the overall authentication mechanism, potentially slowing down domain operations.

Now let’s check what every single step does and how it appears from a network perspective with the help of our good friend Wireshark. You can find the PCAP file I’m using as example right here in the Wireshark samples page. I’m using the krb-816 sample.

Authentication Service - Request (AS-REQ)

The Authentication Service - Request (AS-REQ) is the first step. It’s also called “Pre-Authentication Step”. You can see it by opening packet number 3 of the sample we are analyzing. Here we have a packet which holds two pieces of information. The first piece can be found inside the “padata” header and contains a timestamp encrypted with the NTLM hash of the user’s password. The second piece is inside the “req-body” field and contains cleartext information regarding the username, the domain, the client hostname and so on. Let’s take a deeper look.

Kerberos

as-req

pvno: 5

msg-type: krb-as-req (10)

padata: 2 items

PA-DATA PA-ENC-TIMESTAMP

padata-type: kRB5-PADATA-ENC-TIMESTAMP (2)

padata-value: 3049a003020103a106020400a2f790a23a0438233b4272aa…

etype: eTYPE-DES-CBC-MD5 (3)

kvno: 10680208

cipher: 233b4272aa93727221facfdbdcc9d1d9a0c43a2798c81060…

PA-DATA PA-PAC-REQUEST

padata-type: kRB5-PADATA-PA-PAC-REQUEST (128)

padata-value: 3005a0030101ff

include-pac: True

req-body

Padding: 0

kdc-options: 40810010

cname

name-type: kRB5-NT-PRINCIPAL (1)

cname-string: 1 item

CNameString: des

realm: DENYDC

sname

name-type: kRB5-NT-SRV-INST (2)

sname-string: 2 items

SNameString: krbtgt

SNameString: DENYDC

till: 2037-09-13 02:48:05 (UTC)

rtime: 2037-09-13 02:48:05 (UTC)

nonce: 197451134

etype: 2 items

ENCTYPE: eTYPE-DES-CBC-MD5 (3)

ENCTYPE: eTYPE-DES-CBC-CRC (1)

addresses: 1 item XP1<20>

HostAddress XP1<20>

addr-type: nETBIOS (20)

NetBIOS Name: XP1<20> (Server service)

Don’t worry, we are not going to focus on every single byte of the packet, but there are a few fields you have to understand:

pvno: stands for Protocol Version Number, which is version 5 (the recurring KRB5)msg-type: this line tells us this is akrb-as-reqAS-REQ Kerberos packetpadata: holds the Pre-Authentication data. Here we have thePA-DATA PA-ENC-TIMESTAMPsection. Which type of data this section holds is explained by thepadata-typefield, that tells us it’s a “kRB5-PADATA-ENC-TIMESTAMP”, our encrypted timestamp. The encrypted value is held by thepadata-valuefield of this sectionreq body: this is where the cleartext part of the request is keptkdc-options: this is a collection of flags used to enable certain features for the ticket which will be returned by the KDC (spoilers)cname: this section holds the username the client is trying to authenticate. To be more specific, the exact username in this case is “des” and the data is held in theCNameStringfieldrealm: Realms in Microsoft’s Kerberos implementation are the domains. This is the domain name in the netbios format. Its value is “DENYDC”sname: this section holds the service the client is targeting. Since this is an AS-REQ packet, the service will be the krbtgt (which is the domain user who manages most of the Kerberos operations, we’ll get to him later) of the domain (DENYDC)till: (valid unTILL) this is the expiration date of the ticket which will be issued by the DC (spoilers)rtime: this is the absolute expiration time of the ticket which will be issued if the renewable flag was set (other spoilers)addresses: this section contains the host address. In this case the address is a NETBIOS type address, as specified by theaddr-typefield, and its value is “XP1”, which can be read in theNetBIOS Namefield

Upon receiving this packet the DC reads the username of the user from the cname section, takes his hash from its local database and tries to decrypt the value held by the padata-value field of the PA-DATA PA-ENC-TIMESTAMP. If the decryption succeeds and the timestamp is valid (valid == the time difference is less than 5 minutes, by default), the next step of the Kerberos authentication mechanism begins.

The key takeway here is the fact that this entire step relies on the secrecy of the NTLM hash, not the password, nor the timestamp. Obtain a valid NTLM hash and you can do some nasty stuff, but we will have a look at it later, let’s move on to the second step.

Authentication Service - Response (AS-REP)

The Authentication Service - Response (or Reply, the RFC uses both), aka AS-REP, is the packet the DC sends right after a valid AS-REQ has been received and decrypted. Through this packet the DC issues to the client what’s known as a Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT). The TGT is a piece of information tied to the identity of the user who requested it. Part of it is encrypted using the NTLM hash of the krbtgt domain user. As we said before, krbtgt (pronounced kərbɪtɪdʒɪtɪ’, change my mind) is a very special account used by the DC to manage certain Kerberos operations. It’s considered a High Value Target (HVT) by attackers as compromising it destroys the trust foundations upon which Kerberos itself is built. Let’s examine the AS-REP packet, which is number 4 of our sample.

Kerberos

as-rep

pvno: 5

msg-type: krb-as-rep (11)

padata: 1 item

PA-DATA PA-PW-SALT

padata-type: kRB5-PADATA-PW-SALT (3)

padata-value: 44454e5944432e434f4d646573

pw-salt: 44454e5944432e434f4d646573

crealm: DENYDC.COM

cname

name-type: kRB5-NT-PRINCIPAL (1)

cname-string: 1 item

CNameString: des

ticket

tkt-vno: 5

realm: DENYDC.COM

sname

name-type: kRB5-NT-SRV-INST (2)

sname-string: 2 items

SNameString: krbtgt

SNameString: DENYDC.COM

enc-part

etype: eTYPE-ARCFOUR-HMAC-MD5 (23)

kvno: 2

cipher: 76873a46dedc5b7de4cd702aef30ae79cbd8aa172b9d167e…

enc-part

etype: eTYPE-DES-CBC-MD5 (3)

kvno: 3

cipher: edbcc0d67f3a645254f086e6e2bfe2b7bbac72b346ad05ab…

The fields we have to focus on here are:

msg-type: this line tells us this is akrb-as-repAS-REP Kerberos packetcrealm: this field holds the domain FQDN (DENYDC.COM) to which the client belongsCNameString: this field specifies the client username to which the TGT is issued. The user in this case is “des”. His netbios domain name will be DENYDC\desticket: this section contains the TGT itselftkt-vno: this is the TGT version number, which is 5realm: this is the domain the TGT is valid forenc-part: the firstenc-partsection contains the ticket data encrypted with krbtgt’s NTLM hash. The ticket data is nothing more than the domain name, the username the ticket is issued for and a couple more bytes of stuff (we will see it later)enc-part: the secondenc-partsection contains more or less the same data the firstenc-partcontains, but it is encrypted with the user’s NTLM hash, instead of the krbtgt’s one

Once the client receives the AS-REP packet it proceeds to decrypt the second enc-part and, if the data it contains corresponds to the crealm and the CNameString, the encrypted ticket (that is, the TGT) is imported as-is into the current session. Take note, the client does not and cannot decrypt the TGT, as it is encrypted with krbtgt’s NTLM hash. If the client were able to decrypt it, he could forge a TGT with an arbitrary username and domain. And yes, that’s cool and all, but what’s the purpose of a TGT?

TGTs, as the name suggests, don’t grant access to services, they grant access to other tickets. The type of ticket which grants you access to a service is called TGS, short for Ticket Granting Service. We are about to explain it.

Ticket Granting Service - Request (TGS-REQ)

Say you want to access a share on a domain joined server. First you request a TGT from the DC, then you show that very same TGT to the DC asking for a TGS targeting the CIFS service (the one responsible for filesystem access) of the server on which the share is located. At this point the DC forges a TGS, encrypted with the NTLM hash of the account to which the service is tied (I’ll explain that in a moment) and sends it to the client requesting it.

NOTE: When issuing a TGS, the Domain Controller does not check whether the user requesting it has the clearance to access the service. It's up the the Service Server which will receive the TGS from the client to make sure the user should have access to the resource. That means when you receive an "Access denied" error, it's the Service Server speaking, not the Domain Controller (unless the service is hosted on the DC itself).

Let’s check how a TGS is requested from a network point of view. You can view the TGS request in packet number 5.

Kerberos

tgs-req

pvno: 5

msg-type: krb-tgs-req (12)

padata: 1 item

PA-DATA PA-TGS-REQ

padata-type: kRB5-PADATA-TGS-REQ (1)

padata-value: 6e82041830820414a003020105a10302010ea20703050000…

ap-req

pvno: 5

msg-type: krb-ap-req (14)

Padding: 0

ap-options: 00000000

ticket

tkt-vno: 5

realm: DENYDC.COM

sname

name-type: kRB5-NT-SRV-INST (2)

sname-string: 2 items

SNameString: krbtgt

SNameString: DENYDC.COM

enc-part

etype: eTYPE-ARCFOUR-HMAC-MD5 (23)

kvno: 2

cipher: 76873a46dedc5b7de4cd702aef30ae79cbd8aa172b9d167e…

authenticator

req-body

Padding: 0

kdc-options: 40800000

realm: DENYDC.COM

sname

name-type: kRB5-NT-SRV-HST (3)

sname-string: 2 items

SNameString: host

SNameString: xp1.denydc.com

till: 2037-09-13 02:48:05 (UTC)

nonce: 197296424

etype: 7 items

As we said before, we don’t need to understand every single field in this packet. The important fields are:

msg-type: as the valuekrb-tgs-reqsays, this is a Kerberos TGS requestenc-part: if you skip up to the previous packet and compare thecipherof the firstenc-partwith thecipherof this section, you will notice they store the same value. This is the TGT the client is sending back to the DC while asking for a TGSreq-body: this section holds the TGS request datarealm: this is the domain to which the Service Server belongsSNameString: these two fields hold the service name, which ishost, and the hostname of the Service Server, which isxp1.denydc.comtill: the date until which the client wants the TGS to be valid

Based on the information gathered this far from the packets we analyzed, we understand the user DENYDC\des, logged on the workstation xp1.denydc.com, is asking the DC a TGS to access the HOST service of his workstation. We should point out this far that it’s perfectly possible for a user to access a local service through Kerberos authentication. It actually happens a lot in normal domain operations.

If the TGT provided by the client is valid, the DC should issue a TGS.

Ticket Granting Service - Response (TGS-REP)

We are at the point where the DC has received the TGS request. Let’s check packet 6 and see if it replied with a valid TGS for the HOST service.

Kerberos

tgs-rep

pvno: 5

msg-type: krb-tgs-rep (13)

crealm: DENYDC.COM

cname

name-type: kRB5-NT-PRINCIPAL (1)

cname-string: 1 item

CNameString: des

ticket

tkt-vno: 5

realm: DENYDC.COM

sname

name-type: kRB5-NT-SRV-HST (3)

sname-string: 2 items

SNameString: host

SNameString: xp1.denydc.com

enc-part

etype: eTYPE-ARCFOUR-HMAC-MD5 (23)

kvno: 2

cipher: e63bb88dd1d8f8b5aafe7b76e59e4f42e5e090b679e8a945…

enc-part

etype: eTYPE-DES-CBC-MD5 (3)

cipher: 70e024fdb23293198556e63ca27554cf3dd36d0a548e9215…

The interesting fields here are:

msg-type: this is TGS response, as the valuekrb-tgs-reptells usticket: this section holds the TGS informationrealm: the domain the TGS is issued forSNameString: these fields are identical to their twins from the TGS-REQ packetenc-part: the firstenc-partsection holds the encrypted TGScipher: the encrypted TGS itselfenc-part: the secondenc-partcontains information encrypted with the NTLM hash of the user requesting the TGS. Like the one in the AS-REQ, it gets decrypted by the client which double checks the username and domain

If the response is valid, the TGS is imported into the current session. Imported TGTs and TGSs can be seen from the CLI using the klist command.

Something to consider here is the fact that the TGS itself is encrypted using the NTLM hash of account tied to the service. Active Directory associate services with logon accounts through a particular identifier called Service Principal Name, or SPN. SPNs are written in the following format:

<service class>/<host>[:<port>/<service name>]

MSSQLSvc/workstation.domain.com:1433/MyUberDB

HTTP/server.domain.com

The port and service name are optional. For more information I suggest you take a look at Microsoft’s documentation on SPNs.

What you need to know however is that AD ties the SPN of a service with its logon account. Most of the times this account is a machine account. Machine accounts have long and complex, randomly-generated passwords. But what happens if a SPN is tied to a user account? Humans are often sloppy and their passwords can be easily guessed (or cracked). As we said before, the content of a TGS is deterministic and the client knows it, which means we can try to bruteforce it by trying to decrypt it and comparing the result with the data we know. No shit Sherlock, you just re-discovered Kerberoasting. Don’t worry, we will have a look at attack techniques in later posts.

Now, what is it we need to do with this TGS thing?

Application Server - Request & Response (AP-REQ & AP-REP)

I won’t go too much into details on how this part of the authentication works as it’s not very interesting from an offensive perspective (plus, this post is getting long. And I’m getting bored. Yay for self-discipline). There are some insights, but we can skip them for now as we will get to them when discussing Silver tickets (spoilers!). What you need to know regarding this part of the authentication is that once the client holds a TGS for a particular service, he can use it to prove to the service his identity (well, in theory).

End of the beginning

Ok, I think it’s enough for this first post. In the next one we will take a look at how the first and second step of the authentication process can be exploited by an attacker. See you soon.

last, out.